In a world awash with photos shared on social media, the potential for a Photoshopped image to misrepresent real life to a massive audience is greater than ever.

To maintain integrity, news organisations have to police their own photographers, as well as authenticate pictures they source from the public.

Using Photoshop to fake elements of an image can cost a news photographer their job, as freelancer Adnan Hajj found out in 2006 when Reuters discovered he had artificially exaggerated the dark smoke created by an Israeli airstrike on Beirut, Lebanon.

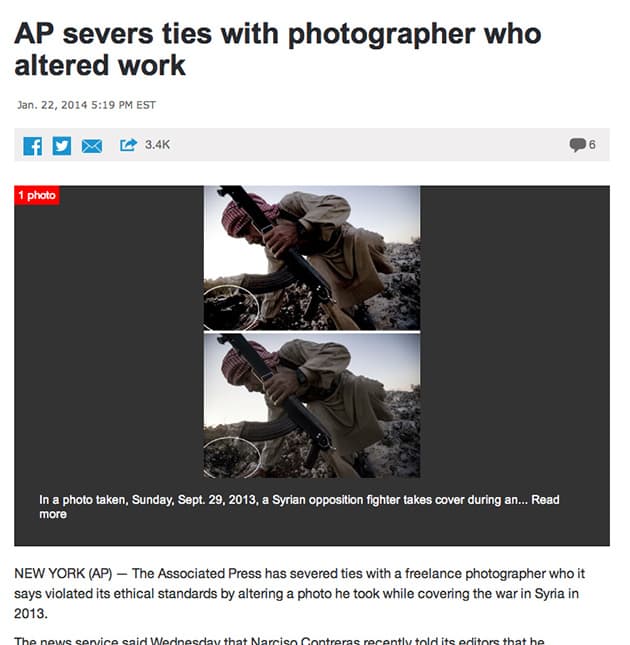

More recently, Associated Press severed ties with Narciso Contreras who had captured an image of a Syrian opposition fighter taking cover from government forces in a mountaintop village in 2013.

The Mexican had used software to remove a journalist’s video camera in the corner of the frame – by cloning other pieces of the background and pasting them over the camera.

The Mexican had used software to remove a journalist’s video camera in the corner of the frame – by cloning other pieces of the background and pasting them over the camera.

The war photography faux pas involved only a corner of the image with little news importance, yet it violated the agency’s ethical standards and breached the agency’s call for truth and accuracy. Explaining his actions, the former Pulitzer Prize winner said he believed the video camera might ‘distract viewers’, adding that he regretted the decision and felt ashamed.

Adding smoke for greater visual impact is not new, though. In fact, such trickery pre-dates digital. Among wartime photos falling victim to darkroom jiggery pokery was a famous shot of Russian soldiers hoisting the Soviet flag over the Reichstag in Berlin, Germany, in May 1945. It was captured by Ukranian-born photographer Yevgeny Khaldei. Auctioning Khaldei’s Leica III camera last year, Bonhams said, ‘The soldiers in Khaldei’s photograph are not the original men and the image has been altered to add more smoke…’

[Photo, courtesy Bonhams]

By comparing different versions of the image, it could be seen how dark smoke was later added to the image, seemingly to add drama to the scene. Further editing took place before it was published, reportedly to remove a watch worn by one of the soldiers, because it was believed to have been looted.

Yet, judging whether a Photoshopped image has altered the integrity of a shot is a subjective process, and may have been done with no intention to hoodwink the viewer.

In 2009, a Ukrainian photographer defended digital manipulation of an image that led to his disqualification from the prestigious World Press Photo competition. Stepan Rudik, a winner in the Sports Features category, admitted to digitally removing part of a foot of a person seen in the background of one of his entries.

Defending his reputation as a reportage photographer, at the time Rudik told AP he did not dispute the jury’s decision, but added, ‘It is clear that I haven’t made a significant alteration or removed any important informative detail. The photograph I submitted is a crop and the retouched detail is the foot of a man that appears in the original photograph but who is not a subject of the image submitted to the contest.’

World Press Photo has since tightened its rules – even commissioning a report into accepted manipulation standards across the industry – but it seems some photojournalists still struggle to distinguish good Photoshopping from bad, or are simply not listening.

Last month, organisers were forced to prevent 20 photos from proceeding to the final round of its 2014 contest, after independent experts analysed all the image files of each suspect entry. Though World Press Photo believed there were ‘no attempts to deceive or mislead’, it said there was an ‘urgent need’ to create a ‘deeper understanding’ of issues that surround the application of post-processing standards in professional photojournalism.

The more tranquil world of landscape photography has also been marred in controversy. The 2012 Landscape Photographer of the Year winner David Byrne was stripped of his title and £10,000 winnings after judges ruled he had used too much manipulation.

David Byrne’s image originally won him the title Landscape Photographer of the Year 2012, but was subsequently disqualified

Byrne said he did not read the rules, admitting he digitally added clouds and ‘cloned out small details’ on a black & white image of Lindisfarne Castle in Northumberland. At the time, the photographer insisted the changes were ‘not major’ and told AP he received many emailed messages of support since being disqualified. ‘I don’t feel I have done anything wrong with the photo – adding clouds and removing small boats from the harbour in the background was a natural thing to do in my eyes,’ he said.

Organisers ruled that ‘the integrity of the subject must be maintained and the making of physical changes to the landscape is not permitted’. Outlawed editing procedures included removal of fences, moving trees and stripping in sky from another image. Byrne admitted, ‘Unfortunately, I did not read the regulations and certain editing, such as adding clouds and cloning out small details, is not allowed.’

Writing on his website after losing the title, he said, ‘While I don’t think what I have done to the photo is wrong in any way, I do understand it’s against the regulations so accept the decision. I apologise for any inconvenience caused.’

Photoshop at 25: Fashion, Beauty and Celebrity

In the world of beauty, fashion and celebrity photography, Photoshop occupies a curious and unique dual space, where it seems to be both a ubiquitous presence and a dirty word.

It’s often referred to as ‘airbrushing’, though a physical airbrushing tool is rarely used these days. Airbrushing has become a catch-all term referring to the practice of ‘touching up’ photos of celebrities and fashion models to slim figures, remove blemishes, smooth skin tone and perform a seemingly endless list of other tweaks and edits.

For some, it’s as much a part of the glamour photoshoot process as make-up, posing or lighting, while for others it’s a symptom of celebrity culture, aggressive normalising of beauty standards and harmful body image, especially for women.

It’s an ongoing debate that shows no signs of disappearing – just yesterday there was fresh controversy as alegedly ‘unretouched’ photos of singer Beyonce Knowles were leaked to a fan website.

https://twitter.com/DailyMailCeleb/status/568136117507088385

It has become a popular stance for celebrities and publications to declare themselves anti-retouching – when actress Cate Blanchett appeared on the cover of the Economist’s Intelligent Life magazine, it was without any digital retouching of the image at all.

Last year, New Zealand singer Lorde tweeted two photos of her from the same concert, one of which had been edited to remove skin imperfections, with the caption: ‘remember flaws are ok :-)’.

https://twitter.com/lordemusic/status/450460437998747650

More recently, there was an outpouring of support on social media for model Cindy Crawford when a non-retouched image of her posing for Marie Claire was leaked online.

Though the photo was initially misidentified as being part of an upcoming Marie Claire series, when it was in fact a leak from 2013, it was still notable for sparking debate on retouching and what ‘real’ women’s bodies look like.

Online, many publications and communities are firmly against retouching. Feminist website Jezebel has made a name for itself in obtaining pre-edit images from photoshoots of stars and comparing them to the final product.

In one notorious instance, the website paid $10,000 for allegedly unaltered images of writer and actress Lena Dunham from a Vogue shoot by Annie Leibowitz, Dunham being a personality who has arguably built much of her identity over not conforming to conventional beauty standards. However, the images received did indicate some alteration of Dunham’s face and body.

‘While Dunham’s images were not drastically altered, it’s important to remember how unforgiving the media is when it comes to images of women,’ said writer Jessica Coen. ‘Men are generally allowed to have pores and wrinkles; women are supposed to be “perfect” – a state that does not exist.’

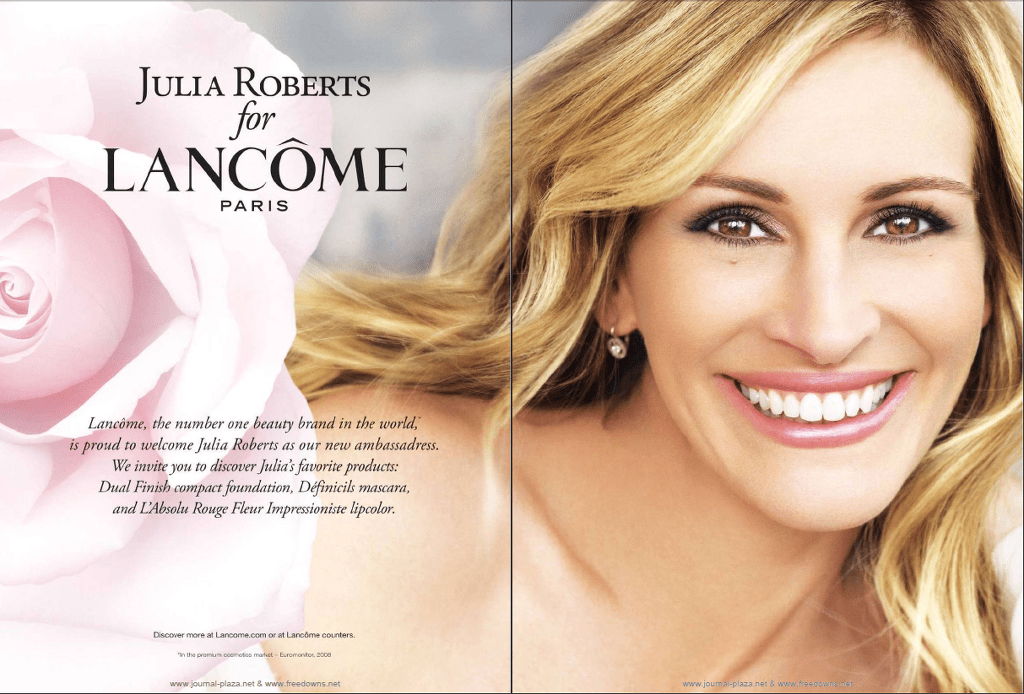

There has even been some governmental kickback against photo retouching – in 2011, the UK Advertising Standards Authority banned an advert for Lancome featuring Julia Roberts, ruling that the flawless skin depicted in the image was simply too good to be true.

Liberal Democrat MP Jo Swinson, who first raised the issue with the ASA, said to the BBC at the time, ‘This ruling demonstrates that the advertising regulator is acknowledging the dishonest and misleading nature of excessive retouching. Pictures of flawless skin and super-slim bodies are all around, but they don’t reflect reality.’

Speaking to photographers who work in the industry, you quickly get the impression that the term ‘game-changer’ is scarcely adequate when it comes to Photoshop. Editorial, beauty and fashion photographer John Wright (www.johnwrightphoto.com) believes that the history of his profession can very much be divided into pre- and post-Photoshop.

‘Photoshop has created an actual era in photography all of its own,’ he told AP. ‘When we say “digital”, the world is meaningless without the association of Adobe Photoshop.’

John also said that the advent of Photoshop as a tool in his industry had levelled the playing field for younger photographers, allowing those with digital skills a new way to penetrate the industry.

‘New emerging photographers can hit the industry harder and at a higher level simply by learning how to use Photoshop. It is one of the cornerstones of our industry now and those who learn how to use it, learn how to succeed.’